The re-written rough bits to date…

On Dragon Weaving

What I Suppose We'd Call the Preamble

Honesty, I haven't a clue why, in February of last year, I found myself pondering the web of dragon mythology that so ensnares the imagination of man. Of how the machinations of my mind materialized the path it would then travel, I've an even clumsier grasp. I believe there is something significant to be found within the folds of fumbled expression held by the essay I had composed. Now, a year later (finding myself in possession of more diversely and formidably equipped faculties), I shall recompose its art and prose, hoping to attain a composition that more capably communicates that which I have to say. It shall be begin with a declaration.

The Introductory Bit

I find them fascinating, the common threads with which disconnected hubs of humanity weave their native narratives. The similitude with which humanity engineers itself by independent means astounds. It warrants remark, in this digitally polarized age of humanity where tribal gutturals dissemble themselves as discourse, the resemblance that runs through the clutch of reflections caught by the collective looking glass.

Such abstraction, dear reader, may satisfy my selfish need to soliloquize; however, it achieves very little in the way of conceptual connection. We need something concrete, an example exhibiting qualities consistent with the previous prose. What though? Which player shall I pluck from the troupe?

Of course it's f$&kin' dragons. I named this f$&kin' thing On Dragon Weaving, how the f$&k would I ever work this f$&ker into an essay befitting of the name were I not, inevitably, about to begin talking about dragons? I mean … I name dropped the little f$&kers in what I believe we've settled upon calling this essay's preamble. Let's hop f$&kin' to it, shall we?

The Bit About Dragons

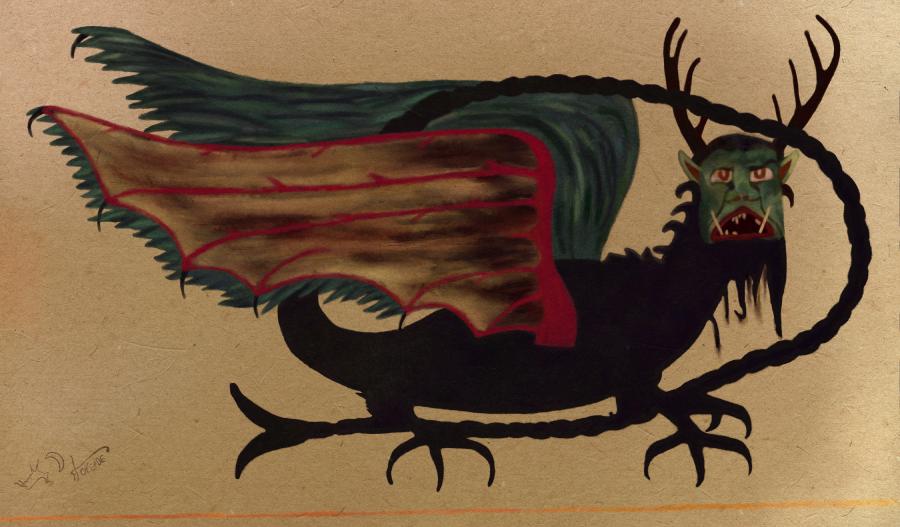

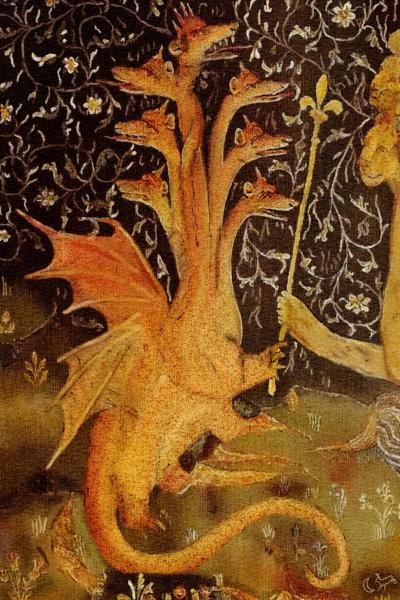

Sooo, I painted us a subset of dragons arbitrarily selected from the set of humanity's mythoi, two of which you've just seen. Since you're reading this in English (one would assume since I'm writing it in f$&king English), there is a strong chance that global Westernization has narrowed the scope of what you think of as being a dragon. The Game-of-Thronesian depiction at the very top likely screams dragon while the fella that follows, the recreation of Bertuch's illustration from the succinctly named Bilderbuch für Kinder: enthaltend eine angenehme Sammlung von Tieren, Pflanzen, Blumen, Früchten, Mineralien, Trachten, induced an assessment of some form or fashion whether he fits the bill. I have no interest in browbeatingly badgering you about what makes a f$&king dragon. I simply thought I oughta point this out and inform you how this essay shall define one. It basically boils down to this: if it's a giant serpent, you can probably get away with calling it a dragon.

I originally began the globetrot in Ancient Egypt; however, taking what I've just relayed into consideration, I think Ancient Greece may be the better initial destination. The reasons are threefold:

⑴ Those for whom the previous passage applies likely received a western education that included at least a little taste of Greek mythology; and, the backbone of Greek mythology is a dragon bone.

⒝ The etymological origin of dragon is the f$&king Greek word drakōn.

(𒄩𒂔𒌈) Some Greek dragons had wings, like the burdened beasts Helios had hauling his chariot about the sky ; but, the majority of the little f$&kers looked more like snakes.

Some Old Greek Dragons

Looking like a snake would be totally on-brand for a beastie known to the world as the Lernaean Hydra (which is English for Λερναῖα Ὕδρα) since the word ὕδρα (pronounced hydra) means "water snake" in Greek.

Hera raised this particular hydra for the sole purpose of killing one mighty annoying demigod by the name of Heracles. Buddy's birth-name was actually Alcaeus. Hera sent two serpents to end the boy in his crib. They failed. He'd hoped changing his name to glory of Hera would get her off his ass. It wouldn't. Hesiod's Theogony tells us that the Hydra was the offspring of Typhon and Echidna, two badass MFers, living in the lake of Lerna in the Argolid.

With multiple heads (one of which was immortal … all of which would grow back), poisonous breath, and blood so corrosive it could kill with a whiff, the Hydra was f$&kin' fierce. King Eurystheus gave Heracles the task of slaying this sucker as his second labor (during his post-murdered-my-wife-and-children atonement tour). They battle. Heracles wins. Yada yada yada let's move on I'm bored.

The kētŏs or κῆτος (latinized as cetus) I have to show you appears to exhibit a few more physical similarities we might expect from a western dragon (I mean … compared to a snake).

The depicted mosaic was discovered in the floor of an ancient Kaulonian residence now referred to as the House of the Dragon. His attack position pose would suggest that this little fella served as the last line of defense against malevolent forces for the adjacent banquet's airy ambience. The Museo archeologico dell'Antica Kaulon, the mosaic's current home, describes the discovery as, "a polychrome mosaic depicting a sea dragon and … framed by a pattern formed by sea waves."

Let's review. The Lernaean Hydra looked like Hera tied herself a handful of water snakes in an overhand knot like they were auditioning to play opposite of that little, problematically portrayed Japanese Beetle in an episode of The Blue Racer. The Cetus, by comparison, looks all kinds of dragonish. The museum calls him a sea dragon and his place of birth the House of the Dragon. What about a creature whose name f$&king ends with Dragon?

Meet the Colchian Dragon (Δρακων Κολχικος), guardian of the Golden Fleece until Jason and his merry band of Argonauts came calling.

So … yeah … he looks like a f$&king snake. Like I said, if it's a giant serpent, you can probably get away with calling it a dragon. They are all dragons. Just go with it.

Some Old Egyptian Dragons

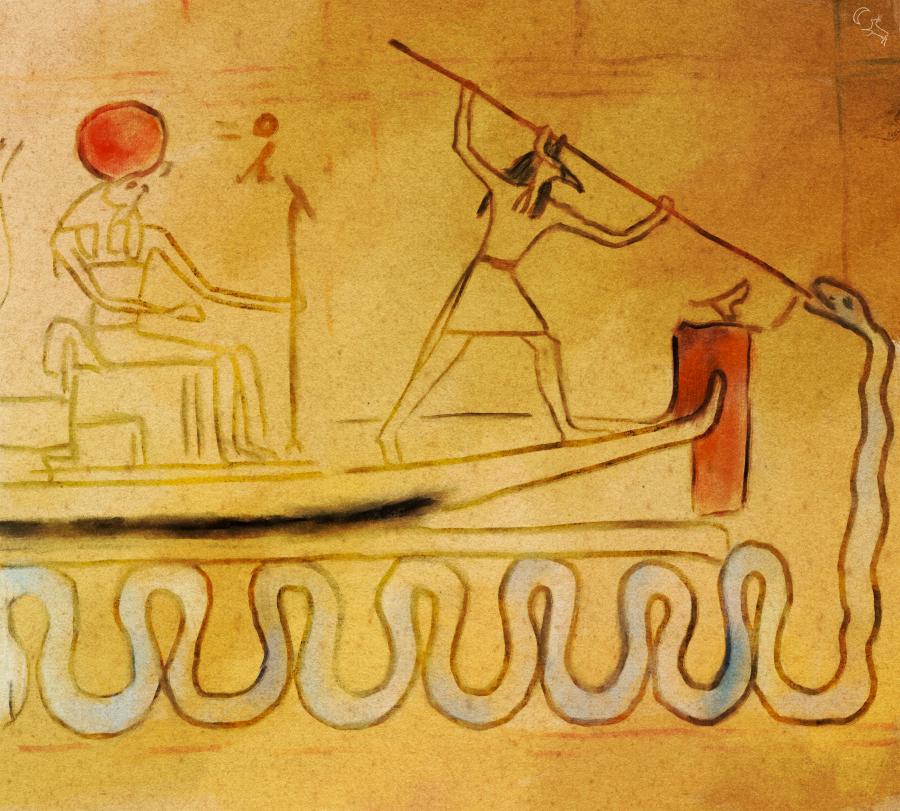

Leaving Ancient Greece in the rearview, we'll now drop our bucket deep down within the well of humanity to probe Terrestrian time before the Biblical flood. Like Johnny Cash, we're going to Memphis, in Ancient Egypt, to have us a look-see at Apep (pronounced 𓌇𓊪𓊪𓆙).

Mention of this particular deity began appearing early in the 22nd century BC as the sun was setting upon the authority of the Old Kingdom. As chaos incarnate, oppugnant to order and light, no doubt Apep was frequently sighted walking in Memphis near the collapse of the Eighth Dynasty. And get this, when Isis, Set, and Ra jacked Apep (as part of their Egyptian power grab), tossing him into the underworld … Apep was having none of it. Every morning thereafter he'd make his way back to the horizon, ahead of Ra, and force that f$&ker to defeat him in battle just to put the sun in the sky. And in the event of a solar eclipse … an eclipse meant that Apep managed to swallow that f$&ker … the sun returning to the sky only after Ra's companion gods manage to topple Apep and cut open his stomach.

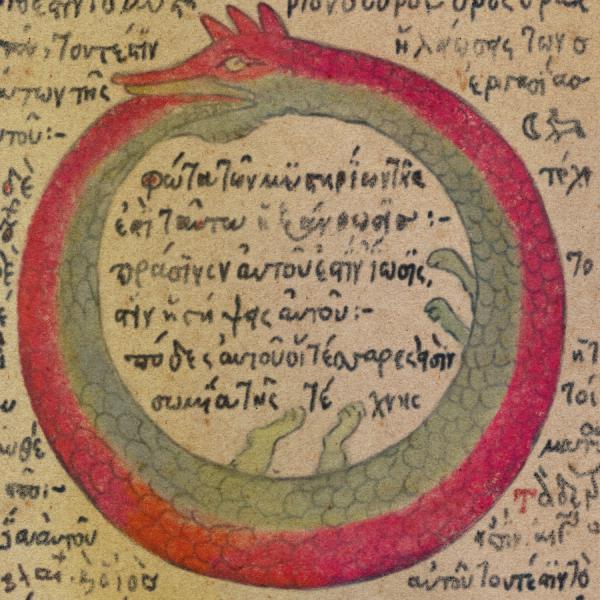

Before we exoduse ourselves out of Egypt, we simply must allow ourselves a proper peep at the world's most interminable orbiculate ophidian, Ouroboros.

A manifestation of the snake god Mehen, Ouroboros may be found inscribed upon the shrine of a sarcophagus as part of the Enigmatic Book of the Netherworld where he represents the beginning and the end of time.

Drawings of Ouroboros would later begin popping up in early alchemical texts like that of Cleopatra the Alchemist, whose work The Chrysopoeia of Cleopatra contains an illustration (not pictured) of the serpent along with the words ἓν τὸ πᾶν (the all is one). The inside of my left leg happens to have this very same illustration (also not pictured) just above the ankle.

Chuck yourself a dart at any wall-hung world map and chances are you'll strike land where Ouroboros dwells. In Norse mythology, exempli gratia (the WordHippoist's for example), he appears as Jörmungandr, the World Serpent–who would grow so large he could encircle the world, grasping his tail in his teeth. Come Ragnarok, it is the poisonous breath of the Midgard Wyrm that kills the mighty Thor.

Some Western Dragons

Germanic myth, Norse inclusive, is simply dripping with dragons. Just look at the Vikings … I mean … they sailed f$&king drakkar.

The dragonhead(s) carved into the stem of these large longships were said to offer protection from evil spirits while at sea. Such power did these wooden drakes possess that Icelandic code of the time, Grágás, bade the Vikings remove any such dragonhead upon their return so as not to intimidate the spirits of their native land.

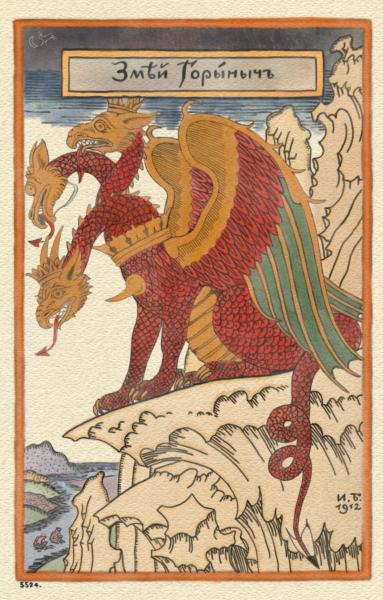

The three carved heads on the ship above identify the bow-based bulwark as a dragon named Zmey Gorynych, let's gallantly gallivant into Garðaríki for a formal introduction.

Garðaríki, by the way, is Old Norse for Kievan Rus'. The Garðar were the Rus' people, Norsemen that had decided to pop on over and take up ruling the river routes between the Baltic and the Black Seas. You zmey have deduced from all those f$&king letter 'Y's, we've crossed over the Germanian border into Russian folklore territory.

Zmey was all about the bylina (Russian heroic poetry). Totally tracks that he would frequently transform himself into a handsome youth to engage in the art of seduction.

Don't let his pervish proclivities prevaricate (yeeesss … I f$&king see the problem … but WordHippo sticks that sh$t in my head … and I can avoid alliteration like Murphy can avoid running head first into a thumpish engagment with the thick, full-length windows that monopolize wall space around here when she's so f$&king excited she can take no more).

Zmey is a proper red-scaled, fire-breathing western dragon with blood so poisonous the Earth itself will refuse to absorb it. This little f$&ker would even go all eclipsical from time to time by taking a bite out of the f$&king sun.

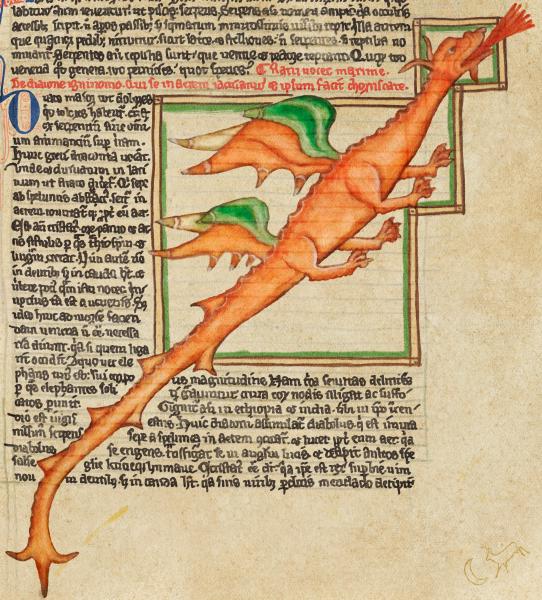

A dark age development, the western dragon is typically depicted as large, fire-breathing, scaly, horned, four-legged, bat-winged and in possession of a long, muscular prehensile tail handy for curling up cozily inside its underground lair. Between the eleventh and thirteenth centuries, that dragons were living, fire-breathing creatures was common f$&kin' knowledge.

The first known portrayal of the fully modern, western dragon appears in a medieval manuscript circa 1260ish.

This little f$&ker is the kind of dragon that most of you were probably picturing upon first taking it upon yourself to read this … this what? … whatever the f$&k it is you want to call this thing you're reading now … like right now … like your eyes line up with this blinkity f$&king cursor now … like *slap* *brief pause* *blinky eyed head shake* … what say we head east and have a look at what the rest of you were picturing.

Some Eastern Dragons

While the Western dragon roots itself to the hero-versus-giant-serpent motif of Proto-Indo-European mythology, it is the Chinese dragon that is birthed by Proto-Sino-Tibetan mythology. From what I've gathered after a seriously soft amount of internet research, the linguistic trip taken by the Western dragon from the Proto-Indo-European word *derḱ- to the Modern English word dragon has a parallel in that taken by the Chinese dragon from the Proto-Sino-Tibetan word *rŏŋ to the Modern Chinese word lóng (pronounced 龙 … or possibly 龍).

The dragon's permeation of East Asian culture is next level. The legendary Chinese sovereign, Huangdi, was said to have taken the form of the Yellow Dragon to ascend to heaven. As the Yellow Emperor is seen as an ancestor of all Chinese people, they sometimes refer to themselves as children of the dragon. In Chinese popular religion, the Yellow Dragon would become one of the five deities composing the fivefold manifestation of the supreme God of Heaven.

Another of the five, the Azure Dragon, would find himself depicted on what would become China's first national flag, that of the last imperial dynasty, the Qing.

Traditional Chinese architecture calls for the erection of a spirit screen, or screen wall, for keeping out evil spirits. Take this concept, toss in a dragon motif, imperialize it, and you've got yourself a Nine-Dragon Wall perfect for placing in one of the imperial gardens or palaces you happen to steward.

The dragons battling it out below over the flaming pearl depict two-sevenths of the Nine-Dragon Wall found in the Beijing-based former imperial garden, Beihai Park.

The prickly pair have good reason to covet this fiery little orb. These little treasures are guaranteed to be holding some high-value commodity–wisdom, power or prosperity, perhaps. Maybe something tangible like thunder or the moon. If it's top shelf, the pearl may embody immortality or even the universal Qi, progenitor of all energy and creation.

As the Indo-European mythologies would emerge, so would the Sinon-Tibetan. Take one part Chinese dragon, one part native legend, stick the parts together, and you'll have yourself a Japanese dragon not unlike the one Hokusai painted onto the ceiling of the Higashmachi festival float in 1844.

It's the three toes on the feet of this handsome fella, along with his slender serpentine physique, that give his origin away. As it happens, the number of toes kinda became a thing. During the Zhou dynasty, this number came to represent rank, therefore most Chinese dragons you come across are gonna have a full five toes. The working theory in Japan, however, was that all dragons were of native origin with three toes per foot. If a dragon wants to leave Japan, it can expect to sprout some toes. The greater its distance from Japan, the more appendages it shall acquire. The toe count gets capped at five when a dragon reaches China.

Operating under this logic, it totally fits that Korea would be chock-full of four-toed dragons like the Blue Dragon in the Koguryoan mural.

Of course, the Koreans believed the four toes on their dragons clearly demonstrated their superiority to the three-toed dragons of Japan. It's that fourth toe that enables the dragon to clutch those pearls. Note that there are four-toed Chinese dragons. When dragon watching, observe the beard. Korean dragons tend to have long ass beards.

Let's keep heading east, I really want to look at some dragons with whom the descendents of Paleoamerican cultures would become acquainted.

Some American Dragons

Dragons flourished all across the pre-Columbian Americas; however, getting to know them is a f$&king challenge. Genocide and forced assimilation kinda tend to disappear the afflicted culture. Consider the case of the Piasa Bird found in Alton, Illinois.

A pair of these suckers were absof$&kinlutely painted upon the limestone bluffs above the confluence of the Illinois and Mississippi rivers. How do we know? A Frenchman told us what he saw during his 1673 expedition of the Mississippi River. As to what he said, here's the valuable bit:

They are as large as a calf; they have horns on their heads like those of deer, a horrible look, red eyes, a beard like a tiger's, a face somewhat like a man's, a body covered with scales, and so long a tail that it winds all around the body, passing above the head and going back between the legs, ending in a fish's tail. Green, red, and black are the three colors composing the picture.

The 1917 publication from which I've pulled his account also includes a helpful little footnote. See if you can spot the problem:

These pictographs on a rock near Alton, Illinois, were called "piasa" and supposed to represent the "thunder bird." They were quite distinct when described by Stoddard in 1803; when visited in 1838 only one could be seen, of which traces were discernible as late as 1848, soon after which the rock was quarried down.

I mean…

⒜ The account from 1673 doesn't say sh$t about what these things are called.

⑵ The footnote from the publication doesn't say sh$t about who mentioned the things oughta be called piasa.

(ᓭ) They quarried … the fucking … rock.

Before moving on from Marquette's account, I wanna show you the least valuable bit. Picking up where we left off in that first quote:

Moreover, these two monsters are so well painted that we cannot believe that any savage is their author; for good painters in France would find it difficult to paint so well, and besides, they are so high up on the rock that it is difficult to reach that place conveniently to paint them.

I believe the Illini response to this was something like ᐃᒃᓯᕚᕐᓂᖅ ᕿᒥᕐᓗ (pronounced sit and spin).

It gets better.

The painting I recreated is by Herbert Forcade. He made it in preparation for painting the f$&ker back up on that limestone bluff. In 1924, he totally did. In the 1960s, they totally blasted that shit to make way for the Great River Road.

It gets better still.

Curious how the Piasa Bird got its name? Let me tell you. In 1836, local Professor John Russell of Shurtleff College published an article with the deets he claims to have obtained from the Illini. Of the stream below the bluff, he has this to say:

This stream is the Piasa. Its name is Indian, and signifies, in the Illini, 'The bird which devours men.' Near the mouth of this stream, on the smooth and perpendicular face of the bluff, at an elevation which no human can reach, is cut the figure of an enormous bird, with its wings extended. The animal which the figure represents was called by the Indians the Piasa. From this is derived the name of the stream.

Okay, so far, we have a real portrayal of a Native American dragon … given to us by a small-minded Frenchman. We add to this the naming of the thing some one hundred sixty-three years later by a professor from a Baptist college (further confirmed in the footnotes of a book published some seventy-six years after the prof's article). What we seem to be missing is some authentic Illini legend of this creature. Have we one of those?

As it happens, we do have one of those, provided in the very same article that gave us the beast's name. Search the internet for the bird's backstory, and you'll find the Legend of the Piasa Bird repeated in countless places. Why haven't I told you the legend? 'Cause the f$&ker admitted he made the whole thing up. You've got about a 50/50 shot of being told that alongside any given one of those repetitions.

Can you believe the dragon exhibition was originally gonna end here? Exploring the erasure of a people's origin story from the annals of history kinda pulled us off course so I thought it best to square things up by painting one more to pull us back. I then constructed a segue that must make the gods of grammar and style weep (and not in a good way). Easily surpassing the forty word mark utilized by Ulysses to trigger sentence splitting suggestions for me to ignore, this beast also happens to count among its possessions three commas, two dashes, a colon, a pair of parentheses, and my approval (so, I'm keeping it). Allow a little extra time for its digestion. I'm sure it'll be fine.

From a dragon mythologized and then quarried by the white man, as if it weren't but hillbilly graffiti–sold twice for a profit, first as so many slabs of limestone and next as an attraction by the city of Alton–and appropriated by Southwestern High School (home of the Piasa Birds and a standalone replica that spits f$&kin' fire), to a dragon colonialism would not erase: we're heading south to see Quetzalcōātl.

The name Quetzalcōātl is a composition of two Nahuatl language words: quetzal or beautiful feather and coatl or serpent. This fella lay at the end of the mesoamerican feathered serpent's evolutionary timeline. By the time his likeness was being drawn into pages, he had a pyramid dedicated to his worship—the world's largest pyramid. We can probably blame the Toltecs for his naughty noms. They linked war and human sacrifice with celestial bodies. They also anointed Quetzalcōātl the god of the morning and evening star.

The Aztecs maintained his solar deification, along with the death and rebirth associations that came with the position. They did manage to round him out a bit by anointing him the god of learning, science, crafts, arts, and agriculture. Oh, he also created humanity in this fifth cycle of the sun we're currently living through.

How can we know all this about Quetzalcōātl yet remain so ignorant about the Piasa Bird? His stone wasn't quarried. His story, written by native Nahuatl speakers, has been preserved. Moctezuma had himself a f$&kin' library. What I've recreated up there is a page from the divinatory almanac included in the amatl known as the Codex Telleriano-Remensis. Shown on the page are the 14th trecena, Quetzalcōātl, and some gloss that explains his significance.

Towards the Making of a Point

The storyteller spins a yarn for transmitting select information as a recognizable pattern from which meaning may be gleaned. From a tapestry woven with a collection of such threads, one discerns a worldview. The collected tapestries woven by a people constitutes their culture.

The introductory bit waxes poetic regarding the common threads running through tapestries woven independently–threads such as the tendency of a dragon to control the weather, to rule the water, or to temporarily block out the sun. Focusing on commonalities was, perhaps, a bit misleading. While they do, indeed, warrant remark, the common threads within the worldview gallery tend to be structural. We might think of the universally common as the warp threads running through these tapestries.

The tapestry's true value lay in its weft. It's these crossings that capture a culture's unique contributions to the whole of humanity.

In medieval France, one might weave himself a dragon having seven heads and ten horns, and seven crowns upon his heads formed with yarn spun by John while in exile on the little Greek island of Patmos.

In Great Ming China, one might weave himself a five-toed dragon up in the clouds chasing flaming pearls.

Everything old is new. The fibers with which a storyteller spins his yarn are harvested by retting the plants born of seeds dropped by tapestries such as these. The crux of innovation is seed diversity. What might it look like, the dragon one might weave with threads of both Indo-European and Sino-Tibetan origin?